As previously seen on GreenBiz.com

By Bahar Gidwani

Image: Shutterstock/Ferenz

Since Jean Rogers founded the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board in 2011, more than 1,800 stakeholders have participated in its standards–setting process. One hundred-plus industry experts, including me, have joined it as advisers and it has issued standards for 35 of more than 80 industries it plans to target.

SASB continues to move ahead quickly. It expects to complete 45 industry standards by the end of this year. Recently, Michael Bloomberg and Mary Schapiro accepted roles as chairperson and vice chairperson, respectively.

People often ask me if SASB will replace the Global Reporting Initiative, compete with the International Integrated Reporting Committee or eliminate the need for research by socially responsible investment firms and other sources of sustainability information. Based on these questions, I have concluded that very few people actually understand what SASB is or how it fits into the world of sustainability metrics.

I personally believe that SASB is creating a “safe harbor” for nonfinancial, sustainability-related reporting, meaning legal and regulatory protection for companies regulated by the U.S. Security and Exchange Commission.

“The Private Securities Litigation Reform Act provides a safe harbor to companies who disclose forward-looking information that is accompanied by meaningful cautionary statements. SASB disclosures involve information about the company’s ability to create value in the future,” the organization says on its website.

A legal safe harbor is “usually found in connection with a vaguer, overall standard,” according to Wikipedia. If SASB is successful, it will create a safe haven within the vague, diffuse world of nonfinancial reporting, a place where companies voluntarily can use SASB standards as guidance that help them comply with existing regulation.

SASB standards require companies to reveal the items the standards deem to be material and effectively allow them to not disclose other nonmaterial items. Companies that comply with the SASB standard should reduce their chance of being sued by shareholders or examined and criticized by the SEC.

Rough Waters

Why do companies need a safe harbor for their nonfinancial reporting? Take a look at this CSRHub chart showing the number of groups measuring company performance and the types of data they use for each of four areas of sustainability reporting.

There are literally hundreds of groups measuring company performance in each area and they are using thousands of measurement approaches. Even with all this data available, stakeholder groups keep coming up with new types of data they feel they need. The result is that a new measurement system sweeps through the metrics area every few months, creating waves, roiling the waters and buffeting companies with disparate requests for information. Rather than giving out more, better data, some companies “batten down the hatches” and try to wait out the storm.

A way to calm the waters

I think many people initially thought SASB was just going to produce another questionnaire to fill out or box to tick. Instead, SASB is creating standards that help companies comply with an existing SEC law called Regulation S-K. By tying its work into an existing regulatory framework, SASB recruits support from government regulators and a legion of securities lawyers and investment analysts.

The SEC regulates the way publicly traded companies disclose information to U.S. investors. It expects publicly traded companies to reveal any information material to the company’s current or future performance. Before a public company makes a disclosure decision, it generally turns to its auditors and lawyers for advice. A company’s auditors will say if they think they can measure a proposed disclosure item accurately. Auditors can’t “sign off” on financial statements that contain unsupported statements masquerading as facts. A company’s lawyers will warn when they feel that disclosing an item might open the company up to legal actions, either by investors or other stakeholders.

SASB’s disclosure standards define and streamline this process. Attorneys and auditors could insist that companies reveal the things that SASB says they should. Shareholder activists and litigators will probe a company that is not forthcoming. As a result, tens of thousands of U.S. publicly traded companies could start releasing hundreds of thousands of well-defined nonfinancial metrics.

SASB’s standards are unlikely to trigger more shareholder lawsuits than occurred in the past. But if a lawsuit claims that a company failed to reveal material facts relating to its sustainability performance, SASB standards are likely to be referred to in the claim, the defense argument or both.

Building the breakwater

Other groups have created or tried to create sustainability reporting standards. For instance, there are International Standards Organization standards for environmental data reporting (ISO14000) and for more general business sustainability reporting (ISO26000). There are also accounting standards and efforts by various industry groups to organize the data their members gather and distribute.

SASB’s innovation has been to use “social norms theory.” It is “a social norm is a sociological concept that refers to explicit or implicit rules that guide behaviors that occur in a social context … transmitted through formal channels such as organizational policies, or by informal channels such as stories, rituals, role-modeling, or nonverbal communication,” according to the National Social Norms Institute.

For example, in order to study investment banking and brokerage companies, SASB convened a working group of industry executives, investors who were interested in financial companies and other experts. This group decided that investors should be told about nine nonfinancial investment banking and brokerage company issues, such as employee inclusion, which the group defined as the percentage of gender and racial/ethnic group representation for executives and other employees. SASB’s staff then helped design procedures for determining how to count each type of racial and ethnic group and decide which level of a company’s management were “executives.” While the input from SASB’s industry working groups is extremely important, it ensures broad support for its standards through this staff support, evidence-based research, a 90-day public comment period for each standard and review by an independent Standards Council.

The SASB working group sought to identify the data items that would be most important for companies in their industry. In particular, they focused on things that investors already ask for. Issues that 75 percent of the working group members felt were important generally make it into the standard. Some issues that receive a lower consensus receive further research and vetting by SASB’s Standards Council. The resulting list of nonfinancial issues for investment banks was narrow, fairly easy to measure and relatively noncontroversial.

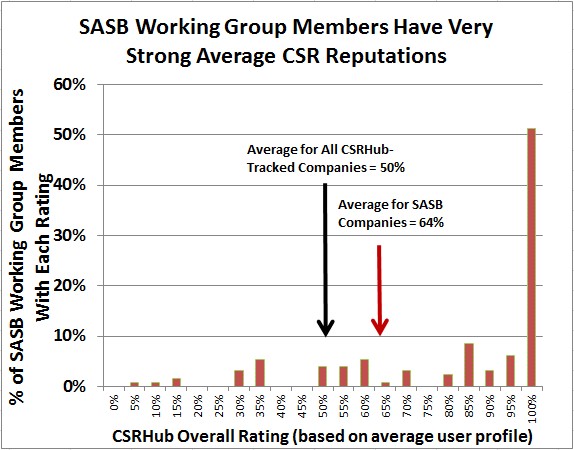

So far, SASB has convened working groups for 50 industries in seven sectors. Each has included corporate professionals associated with a lot of big companies. Even more important, many companies are well regarded for their sustainability reporting. We track and rate most companies associated with SASB working group members. The chart below shows the average rating for these companies vs. all U.S. companies.

The “100 percent” club companies (more than 50 percent of the working group members) are the ones that other companies might like to follow. When a large group of well-respected peers endorse the standard, it becomes a “norm” that other companies will want to join.

This is the first in a two-part series about the use of SASB standards as a safe legal harbor for U.S. public companies. Bahar Gidwani is an adviser to SASB but does not represent the organization.

.png)