The following is part 3 of a 3-part series on “Big Data.”

By Bahar Gidwani

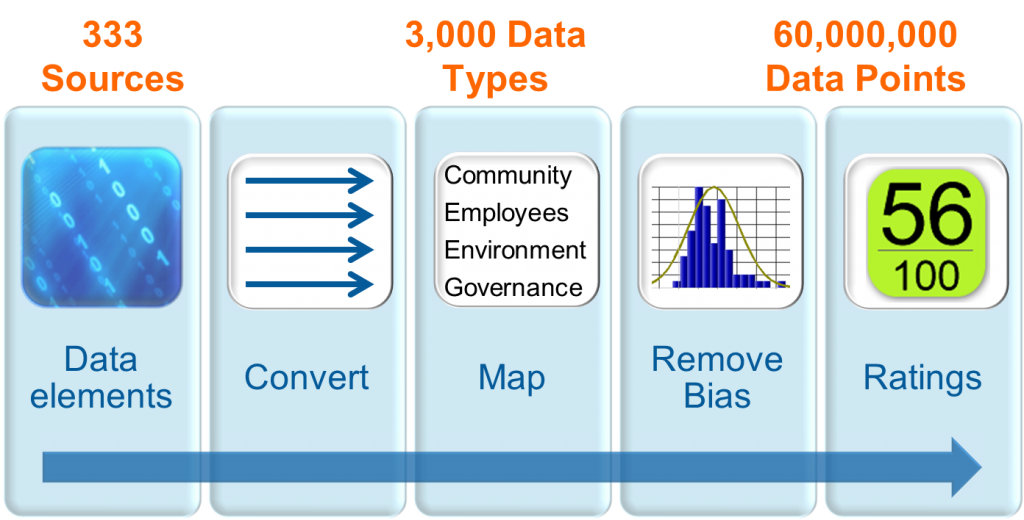

In the past several posts, we have defined Big Data, shown the problems we hope it will address, and described how CSRHub has implemented a Big Data approach to creating corporate social responsibility (CSR) and sustainability ratings. It is time now to discuss the benefits and drawbacks of the “Big Data” approach.

In the past several posts, we have defined Big Data, shown the problems we hope it will address, and described how CSRHub has implemented a Big Data approach to creating corporate social responsibility (CSR) and sustainability ratings. It is time now to discuss the benefits and drawbacks of the “Big Data” approach.

The assumption is that this approach offers many benefits which are not available under traditional analyst-based ratings methods:

- A broad measure of perceived performance. Input from most of the “stakeholders” who evaluate a company’s sustainability performance is captured. Investor input from the ESG/SRI sources, community input from NGOs and government groups, and input from suppliers, employees, and customers via supply chain tools, employee surveys, and product ratings are included. While no one can claim to measure true company performance—no external system can do this, it is possible to give an accurate overall multi-stakeholder-based estimate of how a company is perceived.

- Increased transparency and accountability. The system described automatically reveals to users which sources have reported on each company rated. Via subscriber-accessible tables and custom reports, users can inspect the details of the data gathered. This allows companies and their stakeholders to identify the data elements that affect how they are perceived (transparency) and to respond to or correct data that may not be accurate (accountability).

- Reduced impact from errors and bias. If a source contains a lot of factual errors or an undisclosed bias, this system automatically reduces the weight given to the source. In this way, the effect on our results of poor quality sources is minimized and corrected for systemic biases. Because sources generate their information independently, there is good statistical accuracy for our aggregated scores.

- Regular update and trend tracking. Some sources update their information daily, some quarterly, some only once per year. However, because there are so many sources, our ratings are updated each month. This allows the system to show trend charts that connect actions and outcomes with perception.

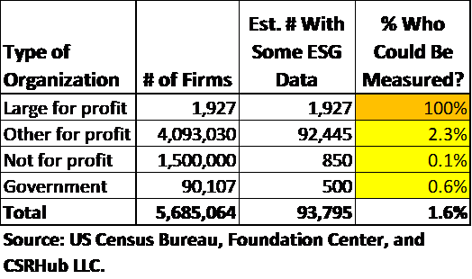

- Broad coverage of industries, geographies, and company types. An aggregation system is dependent on its sources for coverage. We do not yet have full data on small companies or on those in remote geographies or unusual industries. But, the system allows us to use whatever is available. We may not be able to rate all aspects of each new company we add to our system, but any ratings we can generate should be consistent across our system.

We Don’t Yet Measure Thousands of Smaller Corporate, Not-for-profit, and Government Entities

- This approach supports a fourth Big Data “V”—“Veracity.” There is free access to basic ratings information to everyone. As a result, any stakeholder can check scores and audit results.

- Users can adjust ratings to fit their own personal views. There is sufficient data from a wide enough range of sources that we can present alternate sides of many contentious issues. Users can record a profile that adjusts our ratings to match their own view. Users can emphasize the priority of environment, employee, community or governance issues, be in favor of nuclear power or against it, or focus on the risks from mercury in fish. They can then share their personal overall ratings of company sustainability with the other users.

This approach to ratings has a few drawbacks that are common to Big Data systems:

- Perception is not reality. The data that companies self-report is focused mostly on its policies and intent. A company that is good at communicating and “spinning” its story could raise its ratings on the system to a level they do not deserve. Of course, as more data is secured—especially from bottoms up “crowd” sources—this type of behavior will likely eventually be detected. A GovernanceMetric tool called Audit Integrity does this type of sleuthing on corporate financial reports.

- Best practices are not immediately obvious. It is fairly easy to discover that certain activities seem connected with better ratings. For instance, companies who use the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) guidelines or who participate in the UN Global Compact have statistically better ratings than those who do not. However, it is hard to tell if a program at one company has more effect on its perceived CSR performance than a different program at another company. The system described can only provide a base of data—the study and explanation of ratings differences must be done by CSR professionals.

- We cannot correct individual company errors that are found. There are conflicts in the views of disparate sources, on a regular basis. These discrepancies can’t be “resolved” even when we suspect that some are caused by a source’s data collection or analysis error. The best that can be done is to report a suspected error to the source and allow it to research and correct the error, in its own way.

We believe the benefits of using a Big Data approach to measure corporate social responsibility and sustainability performance far outweigh the drawbacks. A Big Data system can be extended to include thousands of smaller companies and organizations. We hope to expand our universe of coverage while we keep narrowing down the “error bars” in our ratings and to see if we can discover some of the drivers that change them. For instance, as we build up a tail of detailed historic data, we may be able to prove that certain actions lead to ratings changes and others do not. As more data become available the approach outlined above can be applied to virtually any company regardless of size and location.

See part 1, Using “Big Data” to Rate Corporate Social Responsibility: One Company’s Approach.

See part 2, A Big Data Approach to Gathering CSR Data.

Bahar Gidwani is CEO and Co-founder of CSRHub. He has built and run large technology-based businesses for many years. Bahar holds a CFA, worked on Wall Street with Kidder, Peabody, and with McKinsey & Co. Bahar has consulted to a number of major companies and currently serves on the board of several software and Web companies. He has an MBA from Harvard Business School and an undergraduate degree in physics and astronomy. Bahar is a member of the SASB Advisory Board. He plays bridge, races sailboats, and is based in New York City.

Bahar Gidwani is CEO and Co-founder of CSRHub. He has built and run large technology-based businesses for many years. Bahar holds a CFA, worked on Wall Street with Kidder, Peabody, and with McKinsey & Co. Bahar has consulted to a number of major companies and currently serves on the board of several software and Web companies. He has an MBA from Harvard Business School and an undergraduate degree in physics and astronomy. Bahar is a member of the SASB Advisory Board. He plays bridge, races sailboats, and is based in New York City.

CSRHub provides access to corporate social responsibility and sustainability ratings and information on 9,200+ companies from 135 industries in 106 countries. By aggregating and normalizing the information from 348 data sources, CSRHub has created a broad, consistent rating system and a searchable database that links millions of rating elements back to their source. Managers, researchers and activists use CSRHub to benchmark company performance, learn how stakeholders evaluate company CSR practices and seek ways to change the world.